wells—where history, folklore, and spiritual energy converge.

Dear Jane,

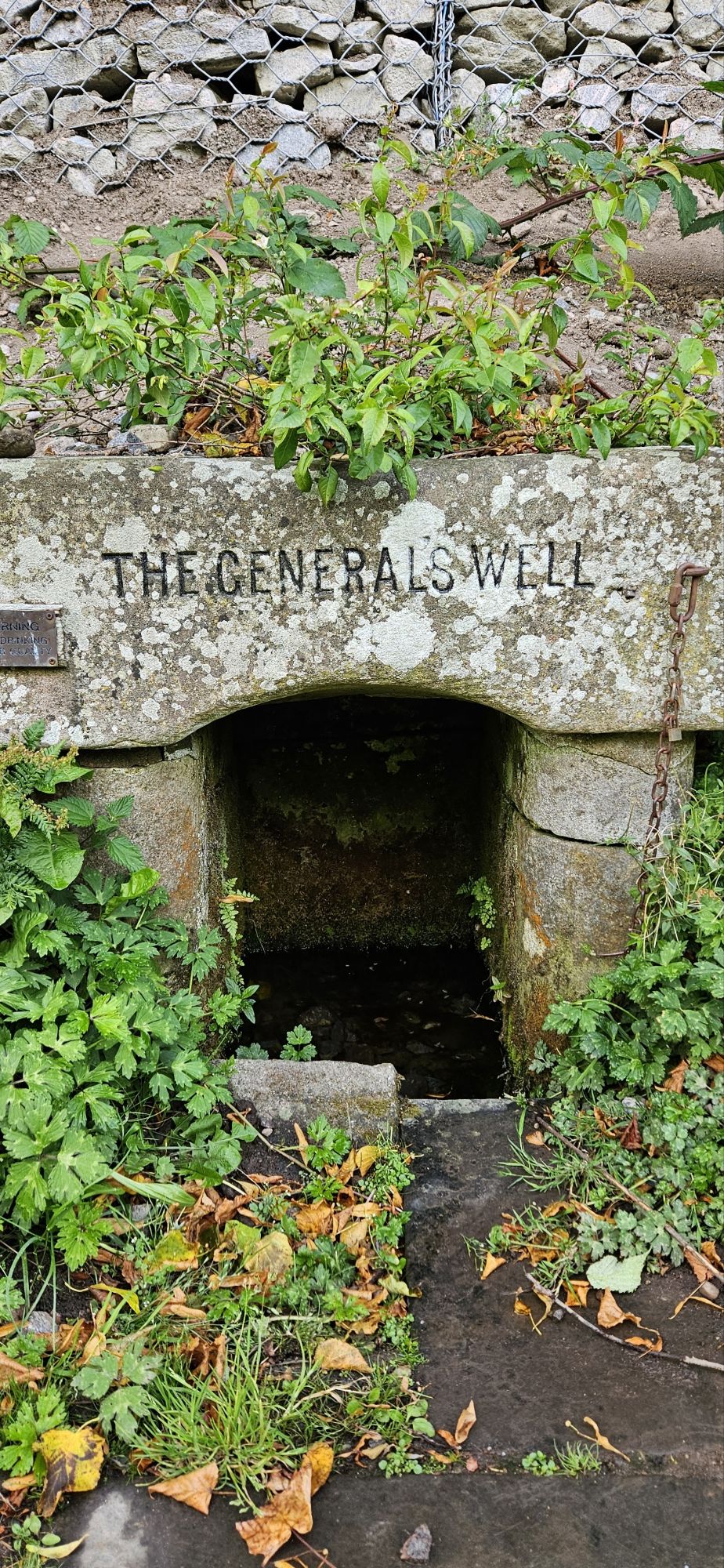

While I was walking along the River Ness, between the islands and Whin Park, I passed The General’s Well. It was on the riverbank, tucked between the main walking path and the iron footbridge I’d just crossed over.

Without Google advising me of its presence, I would’ve walked by without noticing. Its small stone proscenium sheltered a pool of dark water that attracted midges. Despite that, I was reminded of a well I’d visited in Sancreed, Cornwall, England a few years ago, which also featured a stone threshold leading into a pool of water in the earth.

Ancient wells are found across the United Kingdom. Some are man made structures surrounding a spring, like the well in Sancreed, and maybe like General’s Well. With its proximity to the River Ness, it seems more likely that the river water made its way up the riverbank. Some wells are naturally occurring basins in rocks or trees that collect rain or sea water.

In Sancreed, the trees around the well were adorned with strips of fabric in all different colors. That means that well was a Clootie Well, known for its healing power. At Clootie Wells, the idea is that a person will ask the well to heal them, and they’ll dip their cloth strip into the well, then tie it to the tree. The well will heal them in the time it takes for the cloth to rot and disintegrate off the branch.

I was in Sancreed accompanying a late friend’s widow on her errands while she prepared her memorial. Her task list brought us to the now closed Living Well Centre. Elizabeth chatted with her friend who ran the Centre, and I wandered off the grounds, attracted to the nearby trees, which had cloth tied in their branches.

Between the trees stood an opening in the ground, with large granite steps going into the earth. I could step down onto the first one, but the rest were covered in water. An energy beckoned me.

I submerged my hand and made a cup, bringing it to my mouth and face. I drank some water and wiped the rest across my face, allowing the icy dampness to rest on my skin, not absorbing into the pores, just gently clinging to the surface. Though cold, it was comforting. I crawled into the water and down the steps, letting it soak into my clothing, making me heavy like the granite beneath me, and then allowed it to cover my head. Down those steps, in the well, it was dark. There was a faint green glow on the stone walls. I reached out and caressed them. Moss? For an inexplicable reason, it felt so good to be there.

Elizabeth walked up behind me, startling me out of my vision. It had been a very emotional day for both of us. Prior to our visit to the Living Well Centre, we’d visited Bridget’s grave to plant flowers over her. It was my first time seeing a fresh grave in person, and Elizabeth had left me alone to grieve privately.

The indigenous cultures of the United Kingdom believed wells to be points in space where their mortal realm and the spiritual world converged. The spirits helped them heal their ailments, bring good fortune, and sometimes curse an ex-lover or nasty neighbor.

General’s Well was lacking in spiritual energy and actually lacking everything, except a reminder to not drink the water. This well has no lore. The best Google could tell me is that it’s named after a general who lived in the area, and that someone once attached a ladle to it. It’s very weird for an area and country steeped in history.

I did learn that wells can lose their power, and perhaps that’s what happened here. Building something too close to a well can do that. The iron footbridge, called General’s Bridge, is right there. Wells can also lose their connection to the spiritual world if someone misuses it. Examples of misuse include bathing yourself or your animals.

The last reason General’s Well has no known lore could be because of the introduction and influence of Christianity in Scotland. Not all wells met this fate. St. Columba, who brought Catholicism, realized the potential of using wells to convert the locals, and now there are a number of wells along pilgrimage routes. Most famous is the well on the island of Iona, the actual “birthplace” of Catholicism in Scotland.

It’s unlikely we’ll ever know the true history of General’s Well. If you happen to be walking along River Ness, headed towards Whin Park and the Caledonian Canal, try to say hello to the little well.

<3 Katherine

PS – I came across this nugget while I was researching wells for this post: “While it’s not quite a ‘healing’ well, we might turn to the Sancreed Well, aka Well of Chapel Downs, in Cornwall. The local vicar rediscovered it in 1879. Being lost for so long means there is a lack of associated lore, yet visitors report experiencing trance states and visions in the well. Is it a coincidence that scientists recorded the water as having a radiation count some 200% higher than background levels? (Gary 2022: 13)” 😬Read more about Clootie Wells here.